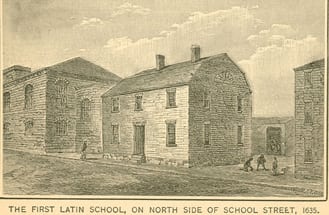

The history of public education in the U.S. isn’t very public. People can point to the first public school in the United States (Boston Latin School, 1635) and say the little red schoolhouse built up from there. But the US education system is more than just an increase in student bodies and rules. As John Taylor Gatto’s The Underground History of American Education argues, the system of education has grown amok, where bureaucracy and big business conspire to keep an underclass of children uneducated and confined to careers as cheap laborers. Teachers, administrators, and social workers are well-meaning in their desire to elevate all children, but they face the odds of a monolithic, unchanging system that forces kids into standardized compartments.

It wasn’t always this way.

Education in the United States was a slow evolution, tied into the changing notions of adulthood and the changing expectations for American workers. States, counties, and cities had different moments on when they made schooling mandatory (in 1647, MassachusettsBay colony required all townships with over fifty households to make schooling compulsory to escape “the old deluder Satan”), but all educators came to believe that children were “blank slates,” needing guidance and tutoring to achieve their full potential as citizens.

Not much has changed in terms of children as tabula rasas. In the 1890s, educator and philosopher John Dewey argued, “Education is a regulation of the process of coming to share in the social consciousness; and that the adjustment of individual activity on the basis of this social consciousness is the only sure method of social reconstruction.” He meant that children needed progressive education, defined as hands-on learning, problem-solving in real life scenarios, and guidance from professional, trained teachers to understand the motives that inspired people like Paul Revere to save his country and people like Marie Curie to innovate beyond the boundaries of established science.

As American labor laws and manufacturing technology eliminated the need for child laborers, school systems expanded. Young adults were now called “adolescents” and were encouraged to use their teens to explore their interests, not find work. Schooling expanded, partially to assimilate new waves of immigrants from Europe, and also to keep children from loitering on dirty street corners with criminals and prostitutes.

But the system has changed. Big business entered school houses in the form of vendors who placed Coke dispensers and IBM computers on campus. Private schools of all types sprang up that promised exceptional schooling if parents were willing to pay for it. Little red school houses also bulged with politicians—in the 1950s, McCarthyites accused teachers of being subversive commies—and education specialists who argued that all children should conform to the same standards or be shuttled into “special education.” The most notable of these programs was No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, under President George W. Bush, which placed special emphasis on testing and teacher accountability.

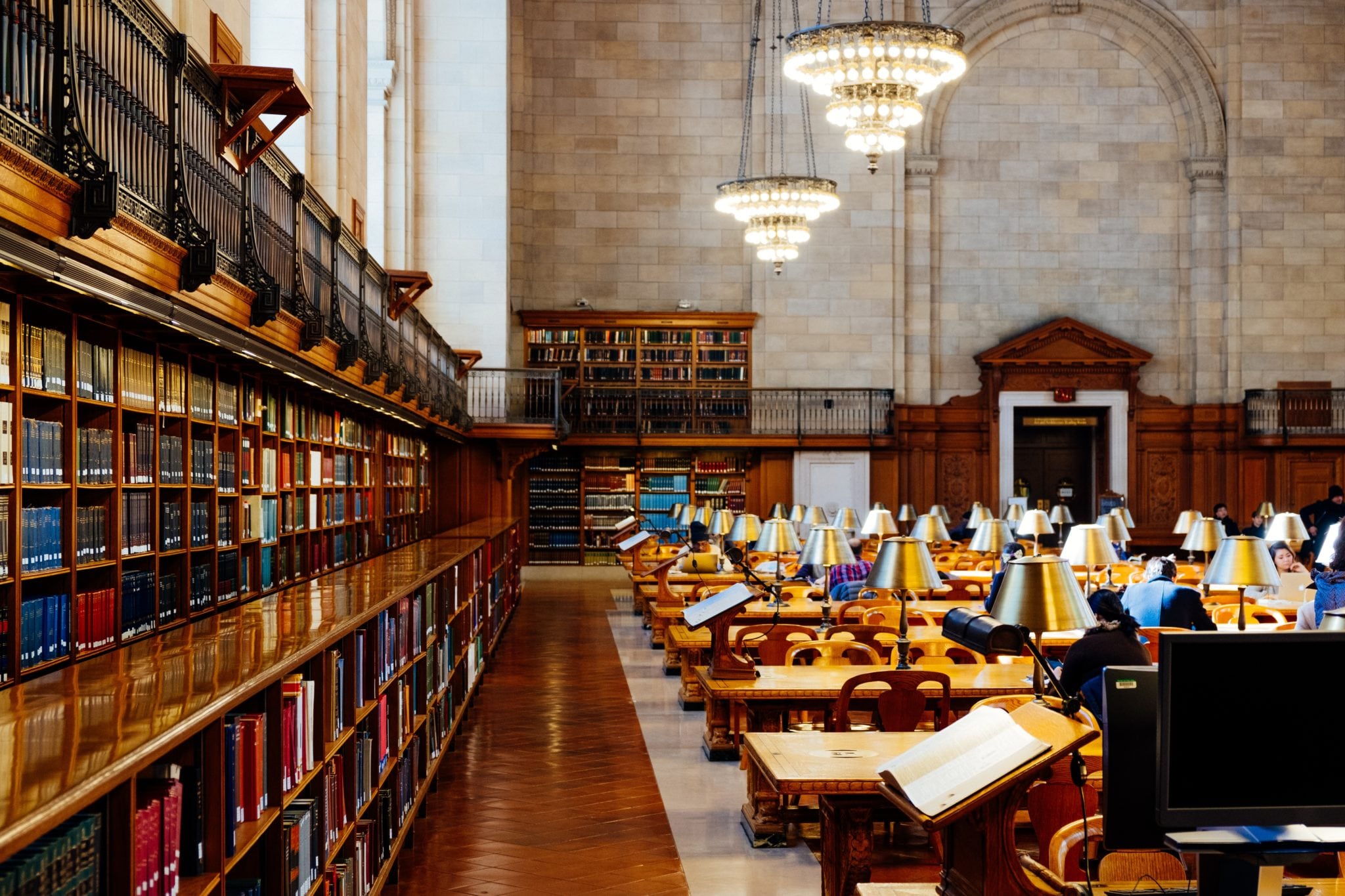

We all know that educating kids is more than just filling in multiple choice bubbles on a Scantron as part of a larger ACT test prep machine. Educators and reformers duke it out over the definition of the words “quality education.” But everyone agrees that many kids need helping hands—resources that can cut through the layers of fighting and politicking. Statistics vary year to year and with different emphasis, but it is clear the U.S. educational system is not as competitive as it once was. They system itself is being “left behind.”

Our kids aren’t geniuses, but they aren’t dumb, either. They thrive on challenges and they don’t quit easily. But they can be discouraged. On the tabula rasa of life, a little penmanship can go a long way.

Who’s there for them?