by Katie Chang

When I was a five years old Asian-American filmmaker, I made my father follow me around our house with his camcorder.

I still watch the video sometimes. It cracks me up, seeing this tiny Asian-American filmmaker girl command the screen with such confidence. In the video, my dad records me as I tell a silly, rambling, completely incoherent story involving my Barbies. I believe it was some controversy between them and my Cabbage Patch Dolls.

A couple years later, my parents got me my own camcorder. They sensed my love for the camera and storytelling. These tools were used every single day in elementary school. With friends, I filmed music videos or mini soap operas with my friends. I gave them directions as I shot some shaky, handheld “cinematography”. Nowadays, it might be considered an artistic choice. I especially loved reenacting my favorite movies and TV shows, like Spy Kids, The Parent Trap, or Phil of the Future.

Something always bothered me growing up though. Too often in those movies, TV shows or music videos I loved, there was no one in the original cast who looked like me. Sure, Spy Kids featured a predominately Latinx cast (pretty revolutionary for the time). But it truly wasn’t until 2005, when The Suite Life of Zack & Cody debuted, that I saw a person of Asian descent in the popular media marketed to me as a typical, Midwestern girl. That actress was Brenda Song, but she played a ditzy, spoiled character that often lacked depth or empathy.

It was palpable to me as a young girl how little the entertainment industry valued people who looked like me, people with Asian heritage.

This fueled my fire. I was determined to become an actress. I would transcend the constant dismissal Asian actors face in Hollywood.

Here, I want to introduce three of my biggest female filmmaking inspirations. The three women that are all of Asian descent. Not only is their art inspiring, but their success in this industry continues to fuel that fire I felt as a young girl.

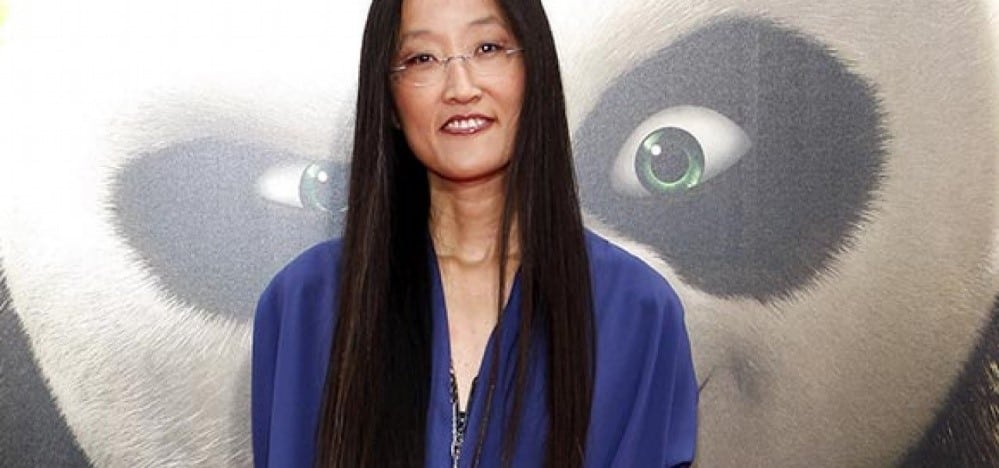

Jennifer Yuh Nelson

Born in South Korea but raised in California, Asian-American filmmaker Nelson comes from a family of illustrators and animators. She served as one of the key story artists for the first Madagascar film. She stayed on with Dreamworks when they began developing the Kung Fu Panda series.

She was the head of story, action sequences supervisor and dream sequence director for the first Kung Fu Panda (2008). Nelson’s producer Melissa Cobb suggested that she take on the daunting role of director for Kung Fu Panda 2 (2011) instead of overseeing only certain sequences. Thus, she became the first woman in history to solo-direct an animated feature film.

Kung Fu Panda 2 grossed $665 million worldwide.

After years of hard work, Nelson became a Hollywood icon. She directed the highest-grossing film by a female director ever (until Jennifer Lee debuted with Frozen). She was also the second woman ever to be nominated for the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature. The first was Marjane Satrapi, who wrote and co-directed 2007’s Persepolis. I HIGHLY recommend watching this film. Due to the success of Kung Fu Panda 2, Nelson was asked to return for Kung Fu Panda 3 and co-direct alongside Alessandro Carloni. The film was released in 2016 and made more than $500 million worldwide.

Nelson is now venturing into live action films. Her first is titled The Darkest Minds and stars with Mandy Moore, Gwendoline Christie, Bradley Whitford and Amandla Stenberg. She is also developing a remake of the 2005 South Korean film A Bittersweet Life with Michael B. Jordan rumored to star.

Mindset behind Nelson’s Success

Speaking to Time in 2017 for their “Firsts” series, Nelson said:

“Everything about me is a little bit unexpected. I’m quiet, a female, and I’m Asian. But it’s actually been an asset for me because people allow me to sort of carve out my own space.”

Nelson’s honesty really stuck with me. The interview largely discusses her surprise at being asked to direct Kung Fu Panda 2. It signals to me that Nelson had been underestimated her entire career because of her Asian heritage and her quietness. But in that lack of attention, she developed her skills. She proved her worth as an artist. She broke through the glass ceiling that held her down.

Nelson certainly is settling into her space nicely and inspiring many young Asian-American girls who want to venture into the world of animation. It is especially inspiring to me. I am currently writing two full length scripts myself, one that is half-animated and one that is fully animated. Nelson’s career and story make me feel like I can achieve anything I want in this industry.

The One Thing I’m Passionate About

I decided to quit all my extra-curriculars and focus solely on becoming a better speaker with acting classes. Though a lot of hard work went into the next four years, arguably I got lucky when I was cast in my first film at the age of sixteen. Granted, the character was based on a real person who was Korean. I had the advantage in terms of auditioning. I’ve reflected on this a lot, and I acknowledge that the character I played in that film was based on a person who is fully Korean. I am only a quarter Korean. This in and of itself is problematic and a form of whitewashing that I benefitted from.

After the film came out, I started to enjoy a burgeoning career. Still, I decided that I wanted to complete my education. I went to college where I studied film and learned more about being behind the camera. I obtained new insights about the history and theory of film as well as screenwriting. My studies encouraged my belief that there should be more people of Asian descent on our screens.

They also revealed to me how rare it is to find an Asian person BEHIND the camera. I realized how even rarer it is to find a FEMALE filmmaker of Asian descent. I have adjusted to being a full-time actress and writer over the course of my college career, especially in the last year. I’ve grown passionate about making connections with and discovering Asian/Asian-American/Hapa female filmmakers (“hapa” is a Hawaiian term for anyone who is of part Asian or Pacific Islander ancestry).

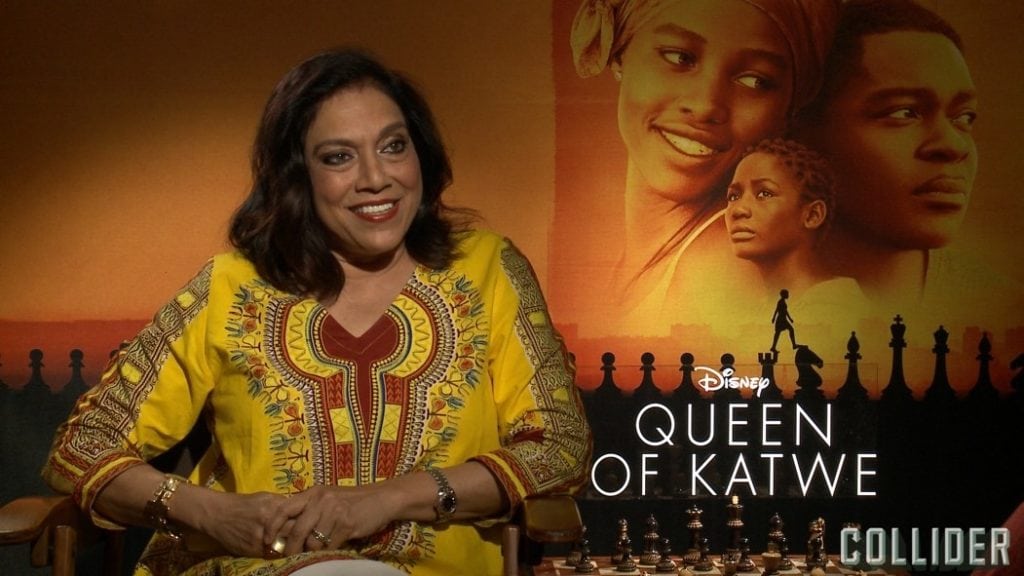

Mira Nair

Nair, another Asian-American filmmaker, was born in India and moved to the United States at age nineteen to attend Harvard. She began her filmmaking career there as a documentarian. In 1988, Mira made the transition to narrative features. She co-wrote and directed the critically acclaimed Salaam Bombay! The film follows the lives of street children in Bombay, India. Most of the child actors in the film were regular children Nair and her team found on the street. After the film debuted, she even created an organization called the Salaam Baalak Trust to help the street children-turned-actors.

Professional success

Salaam Bombay! was an international success, winning both the Audience and Golden Camera awards at the 1988 Cannes Film Festival, two National Film Awards, Top Foreign Film at the National Board of Review Awards and the Jury Prize at the Montréal World Film Festival. The film was also nominated for the Academy Award, Golden Globe Award, BAFTA Award and César Award for Best Foreign Language Film. Nair’s second feature, Mississippi Masala, was released in 1991 and starred Denzel Washington and Sarita Choudhury (Homeland, The Hunger Games) as lovers fighting for their relationship against immense racism and prejudice. Mira also directed Monsoon Wedding (2001), which won the Golden Lion at the 2001 Venice Film Festival. More recently, she completed Queen of Katwe (2016) starring David Oyelowo and Lupita Nyong’o.

In 2016, journalist Kanika Katyal, writing for Youth Ki Awaaz, asked Nair: “When does filmmaking become a political act?” She responded:

“I think filmmaking is a political act, it doesn’t become it. It begins from the inception – What do you have to say about the world in your film? What is your point of view?”

What I learned from Nair

Certainly, there are many filmmakers who did not set out to make overtly political films. Their art has value, and I do not think there is a right or wrong when it comes to the kind of societal message or impact a film should deliver. All I know is that I want to be like Mira Nair. I believe that my films will be at least subtly political because I want to examine, criticize and put the world I’ve grown up in on trial. Regardless of whether the topic covers art or science in the US, politics shape how standards get established. Nair has embraced this reality throughout her entire career.

What do I have to say about the world of my films?

What is my point of view?

These are questions that will stay with me as I take my first few steps towards writing and directing my own work. Today, I feel bolstered and lifted up by Nair’s efforts to make a space for me as an artist.

Kary Kusama

As I am hapa, I felt compelled to lastly feature a mixed director in this post. There’s truly no hapa female filmmaker better than Karyn Kusama.

Asian-American filmmaker Kusama grew up with a Japanese father and a white mother in St. Louis. She studied at NYU, nannying to make money on the side. While nannying, she met filmmaker John Sayles and worked as his assistant for three years while he made the Academy Award-nominated Lone Star. Kusama released her first directorial/writing effort in 2000: Girlfight starring Michelle Rodriguez. The film was Rodriguez’s on-screen debut and follows her as a Brooklyn teen who turns to boxing to work through her troubles. Girlfight won the Grand Jury Prize at the 2000 Sundance Film Festival and garnered further critical acclaim for both Karyn and Michelle. It received accolades from the Cannes Film Festival, Gotham Awards, Independent Spirit Awards, National Board of Review Awards and the Deauville American Film Festival.

Kusama’s next two films after Girlfight were Æon Flux (2005) and Jennifer’s Body (2009). Critics considered both films as financial and creative failures, which landed Kusama in “movie jail.” During this time, Kusama vowed to never make another film again without having control over the final cut. By 2015, Kusama had returned to Hollywood in full force. She debuted The Invitation at the South by Southwest Film Festival to great acclaim and praise. She also began directing television, and since 2015 has worked on Chicago Fire, Casual, Masters of Sex, The Man in the High Castle, Billions and Halt and Catch Fire. Later this year, she will return to the big screen with Destroyer, a film about a detective reconciling with her past starring Nicole Kidman, Sebastian Stan and Tatiana Maslany.

Mindset behind Kusama’s Success

Speaking to RogerEbert.com’s Nick Allen in 2016, Kusama explained her personal influences in her work post-Jennifer’s Body:

“I think for me, over the years I have really had to investigate my personal sorrows and the tragedies that have visited me over my lifetime. I had to really grapple with the fact that while I wish things could be different at times, I ultimately needed to experience the transformation that comes with pain and loss and sorrow.”

Kusama’s work stands out not just because she is hapa, but because she wants to face true, naked pain head-on. Many current-day directors bolt in the opposite direction when confronted by the theme. Furthermore, she dealt with the hell that can be “movie jail.” Female Asian-American filmmakers too often find this as their exclusive domain, especially filmmakers of color. She came out on the other side, full of resiliency and even more-so determined to make art.

I hope you found this post interesting. I highly encourage you to check out works by Jennifer Yuh Nelson, Mira Nair and Karyn Kusama, as well as many other female Asian-American filmmakers I didn’t have time nor space to include here (i.e. Marilyn Fu, Meera Menon, Jennifer Phang, Grace Lee, Yulin Kuang and the up-and-coming Lulu Wang). These women inspire me every single day and I hope you find some inspiration from them too!